…..memory is made, not found and what we remember matters. – Lisa Tetrault

This post is something of a personal reaction to The Myth of Seneca Falls: Memory and the Women’s Suffrage Movement by Lisa Tetrault, so I should start with the most important thing before I go into the wandering digressions. It is a really good book and you should read it.

Some People Don’t Get It

The most negative review on Amazon (a three star) highlights by omission what is really good about the book.

This book does reveal some nuggets of difficult to find information and the author is obviously extremely knowledgable and gifted but the book contains too much run-of-the-mill, feminist cheerleading and the revealing information in the book is revealed in a way that makes it seem as though it was included almost as an afterthought.

The book is overly verbose and should have been half its length but the author has a bad tendency to lapse into moments of drawn out flattery of the movement which we’ve already heard a thousand times. Even though the suffrage movement obviously deserves some cheerleading this book pours on the cheese a bit too much to warrant a higher rating.

The key words in the title are Memory and Myth. Lisa Tetrault’s work is about how and why we make narratives about the past using a reasonably familiar (in some circles) narrative, illustrating its incompleteness and more importantly how and why that particular narrative was constructed.

Historiography

I could see this work becoming not only a standard text in women’s studies or the history of social reform, but also in historiography , which the infallible source tells us is “the study of the methodology of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension in any body of work on a particular subject”.

Tetrault quotes historian Lori Ginzberg:

Every event in history is a beginning, a middle and an end, it just depends on where you pick up the thread and what story you choose to tell.

Sam Gamgee made the same point:

We’ve got – you’ve got some of the light of it in that star-glass that the Lady gave you! Why to think of it, we’re in the same tale still! It’s going on. Don’t the great tales never end?

‘No, they never end as tales, said, Frodo. ‘But the people in them come, and go when their part’s ended

Frodo of course. recognized the essence of historiography in this clip.

Nothing like referring to the world’s greatest bromance in a reaction to a great work on women’s history. Back to the book.

The Myth

The “myth” under discussion in this work is illustrated in the National Women’s History Museum’s Woman Suffrage Timeline (1840-1920).

1840

Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton are barred from attending the World Anti-Slavery Convention held in London. This prompts them to hold a Women’s Convention in the US.

1848

Seneca Falls, New York is the location for the first Women’s Rights Convention. Elizabeth Cady Stanton writes “The Declaration of Sentiments” creating the agenda of women’s activism for decades to come.

Due credit is given to conventions in Worcester in 1850 and 1851, which I have a particular attachment to, but beginning in 1853, the partnership between Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B, Anthony starts to dominate, with Susan B. Anthony taking the limelight. To take a biblical analogy, Elizabeth Cady Stanton would be John the Baptist making Susan B. Anthony, well, you know.

Tetrault’s work is about how that story became THE story. And it is not just about how Susan B Anthony became the main actor in the story, but also about how suffrage becomes the big story about women’s right, white women’s suffrage actually, since the 19th amendment did not help black women vote in the South, where black men had been systematically disenfranchised.

Like The Late Unpleasantness

Tetrault connects the story of the creation of the women’s rights narrative to that of the construction of the narratives that help us remember slavery and the war with many names (Civil War, War Between the States, War of Northern Aggression – personally I prefer The Late Unpleasantness)

The fierce debate – over competing definitions of freedom – took place in the arena of memory. It was not the only arena, but it was a critical one. Because freedom had no inherent self-evident meaning, Americans debated its definition by attempting to define the past. Why had the Civil War been fought? Answers to that question, which varied widely, defined different paths forward. Had it been fought, as freedpeople and abolitionists argued for emancipation? If so that required a postwar political response that validated the needs of freedpeople and invested freedom with significant weight? Or had it been fought, as white supremacists argued, for valor, honor, and states’ rights? If so, that required a postwar political response that elevated the rights of white Confederates over the rights of freedpeople, whose needs were largely erased by such a memory.

More Than A Counter-Narrative

I’m now going to be segueing from reviewing the book to my rambling personal reaction, but to sum up I will react to one of the five star reviews.

The publication of “The Myth of Seneca Falls” is a big event for those of us who like to live in the suffrage world. Professor Tetrault has come up with the first really effective counter-narrative to Eleanor Flexner’s classic “Century of Struggle”.

I really don’t view Tetrault’s work as a “counter-narrative”. It is much more than that. It is a narrative of the making of the received narrative that suggests many other narratives that might be constructed and from there I will move to my personal reaction.

Searching For Margaret Fuller

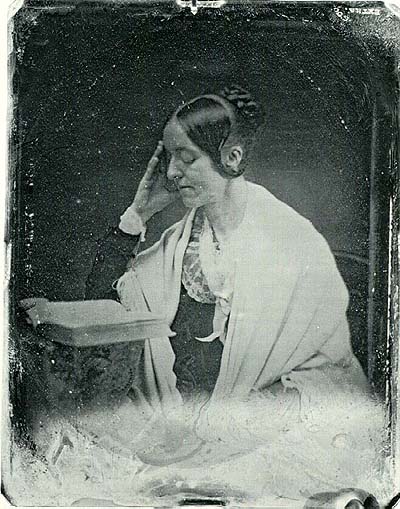

I discovered Professor Tetrault’s work from a hunt that someone had sent me on. The question as I might frame it now, having read Myth of Seneca Falls, was why Margaret Fuller, who, Margaret Fuller scholars consider with substantial support, a women’s rights pioneer of the highest order, whose Woman in the Nineteenth Century was published in 1845 whose Conversations, arguably the 1840 version of second wave consciousness raising groups, included Elizabeth Cady Stanton does not appear in the Timeline.

It really would not be that hard. Between 1840 and 1848, you put in 1845 publication of Woman in the 19th Century. Fuller was in Italy covering and taking a hand in a revolution in 1848 when Seneca Falls took place. She had been invited to preside over the first national women’s rights conference in Worcester in the fall of 1850. Sadly her only participation was in spirit during a moment of silence as she lost her life in the wreck of the Elizabeth, a 530 ton sailing vessel, that grounded off Fire Island on July 19,1850.

Professor Tetrault, answers the question even though her work does not even mention Margaret Fuller. In the received narrative the story really starts in Seneca Falls and focuses on Susan B. Anthony who is first mentioned on the timeline in 1853, but along with Stanton dominates it through the post-Civil War period. The received narrative was largely the creation of Susan B Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton. Not only are they center stage, but there is also a singular focus on suffrage.

Many Narratives

Probably, the most important thing we can learn about history is that there are many valid narratives that can be crafted from the raw material of the past. We can ask different questions of different sources and derive different stories. I think that many people when they encounter this reality find it rather disturbing. I know I certainly did when I asked my father how it was that Robert E Lee, chief bad guy in the Civil War, was accounted a national hero appearing on postage stamps. The budding neoabolitionist never got a good answer from his old man.

Professor Tetrault is an historian and they tend to be a bit allergic to counterfactuals, but as a graduate school dropout who loves Harry Turtledove, SM Stirling and Eric Flint, I’m different. Thanks to her book I am now in the grip of a profound counterfactual. What would have happened if the Elizabeth had docked safely in New York and Margaret Fuller had presided over the first national women’ rights conference in Worcester?

My favorite biography of Margaret Fuller is the one by Thomas Wentworth Higginson and in it he saw her mainly as a woman of action ready to unleash. It is just possible that she might have been able to galvanize a different reform movement than the one that fragmented over votes for African Americans versus votes for women in 1866. In her work she addressed issues of gender, but also of race and class. She was rare among New England Unitarian reformers in having kind words for Irish refugees, then the most despised white people in America.

Higginson’s assessment deserves to be taken seriously, because he, himself, had strong activist credentials – the Anthony Burns rescue, John Brown, command of a regiment of liberated slaves (First South Carolina Volunteers – later 33rd United States Colored Troops).

But maybe it was too soon to have a holistic reform movement and maybe it could have turned out worse – like when Spock and Kirk had to stop McCoy from saving the life of the 1930’s peace activist in The City on the Edge of Forever.

I’m sorry I don’t have the talent to write “The Elizabeth Must Sink”, but I can always hope that a talented alternate history writer might pick it up.

________________________________________________________________________

Peter J Reilly CPA hoped to be an historian, but public accounting has been good to him.

.