This post was originally published on Forbes Sep 30, 2015

Deja vu all over again. Another presidential campaign. Another flurry of concern about “carried interest”. The Cliff Notes version of “carried interest” is that people become partners in partnerships in exchange for future services and get some of their return in the form of capital gains, despite never having contributed any capital. It seems that the practice is most resented when it benefits people running private equity funds – “hedge fund guys”. Believe it or not, you can find a rationale for why this is good thing.

A rather intriguing group called Patriotic Millionaiers explains why they think it is a bad thing.

At least in the summary that Senior Policy Advisor Warren Gunnels sent me, the Bernie Sanders campaign did not make the same mistake. Bernie wants to treat capital gain the same as other income and accordingly makes no mention of carried interest. Jeb Bush has come out in favor of eliminating carried interest in his plan.

Carried interest presents itself as a perfect case study in public choice. The issue matters deeply to a small, well-organized, wealthy group of politically active individuals. The benefits of change, by contrast, are diffuse. Politicians can simultaneously use the issue effectively to extract rents from the one percent and then turn around and use the prospect of reform to energize the base. Whatever the merits of the issue, the positive prediction of public choice theory is clear: legislators will continue to talk about the issue, never quite acting on it, until its symbolic value has dissipated.

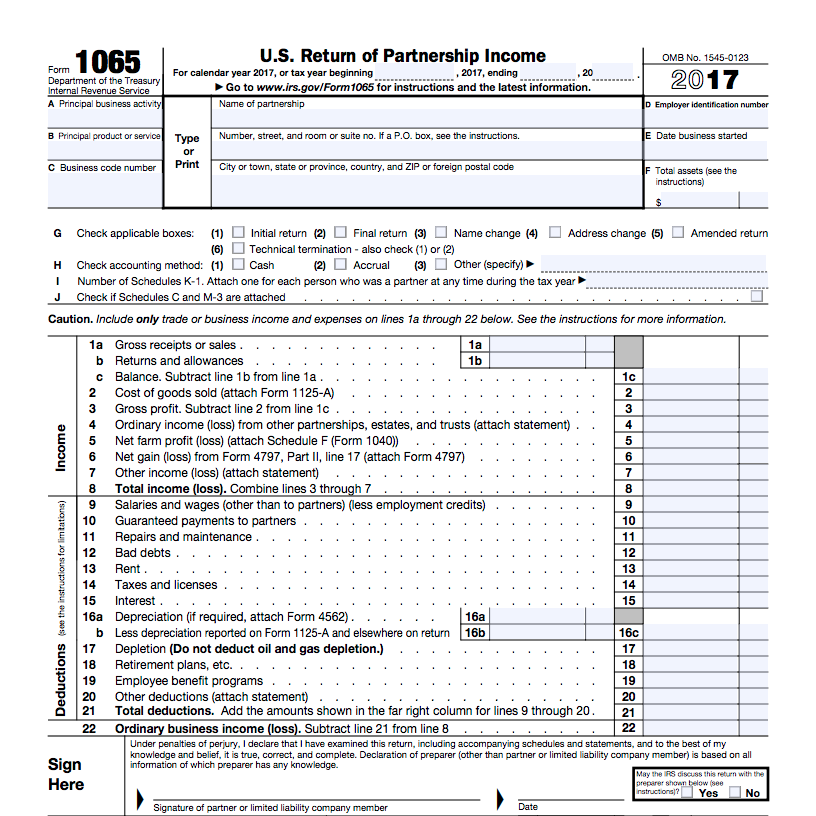

Many partnership tax experts view taxing carried interest as ordinary income is a departure from a basic principle of partnership tax. Subchapter K generally allows character to be determined at the partnership level, and it generally does not inquire into the nature of the contributions of different partners to the enterprise. In this sense it is similar to the tax subsidy for founders’ stock in the subchapter C context, and I am in the minority in finding the subsidy for founders’ stock to be bad tax policy.

The Senate Finance Committee held a closed-door briefing for the committee staff, staff from the Treasury and the I.R.S., and legislative assistants. The Senate Finance Committee passed legislation, dubbed the “Birthday Party” bill, that would have targeted publicly-traded private equity firms. Private equity lobbyists worked to quietly expand the target of the legislation to include smaller partnerships, real estate, venture capital, and oil and gas, all as an effort to gin up opposition to the legislation.

President Obama should resolve the carried interest debate unilaterally by directing the Treasury Department to revise the regulations recently proposed under Section 707(a)(2)(A). The regulations should provide that if a service partner contributes less capital to the partnership than the aggregate amount of capital contributed by taxexempt partners, any allocation of income to the service partner would be treated as compensation for services.

The case for executive action is both pragmatic and principled. Changing the tax treatment of carried interest could raise as much as $200 billion in revenue over ten years—enough to double the amount of federal dollars allocated to college financial aid, for example. Taxing fund managers at ordinary rates on their labor income would correct an injustice that exacerbates income inequality and allows an unnecessary tax subsidy to flow to the richest one percent of the one percent. Taxing carried interest as ordinary income advances efficiency, equity, and administrability. Doing so promptly through executive action would be legal, sensible, wise, and just

I think that interpreting 1.701-2 in that fashion would lead to more damage to other partnerships than proposed Section 710 would. 1.701-2, when enacted, created tremendous concern from the tax community that it gave too much discretion to the IRS in pursuing transactions that it viewed as abusive. In the 15+ years that have followed, practitioners have, more or less, gotten comfortable that that IRS discretion will not be abused. If the IRS now uses that discretion to aggressively interpret the anti-abuse rule in the manner you propose, we’d be back in a world of fear, severely impeding any practitioner’s ability to give comfort on a partnership transaction.

Professor Fleischer’s approach is much more targeted and might not raise the same concerns.

I had a brief exchange with Professor Fleischer. He thought it likely that funds would restructure to take advantage of the 15% rate if Trump’s tax plan were enacted. In an article in the New York Times in June Professor Fleischer wrote that the issue is worth about $18 billion a year.