If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be free and life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands. But if we fall, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science. —- Winston Churchill

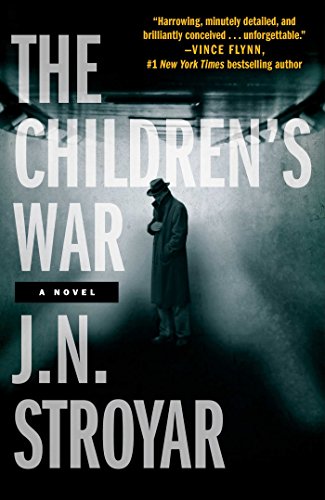

Nowadays, it is fairly easy to find references to prison rape in popular literature. One of the most common is its use by police and prosecutors as leverage to gain cooperation. Works that are about prison, fiction or nonfiction, will almost always refer to it, even, if only to claim that its prevalence is exaggerated, as does the author of Newjack. The Children’s War stands out in the way in which the subject is integrated. The principal character is a male prison rape survivor. The rape and its after effects are a key element in the plot, yet it is not a book about prison rape.

The Children’s War is of the genre known as alternative history. The concept is to set a story in a world that is the same as ours, except for some historic event or events that turned out differently. The author will sometimes posit a mechanism, such as time travel or parallel universes, which causes some of the works to be classed as science fiction. In others, it is simply a “What if?” with no mechanism for getting there. The works of Harry Turtledove, perhaps the premier practitioner of the genre, illustrate both types. In the Guns of the South 20th Century white supremacists travel backward in time to provide the Confederacy with AK-47’s. In Turtledove’s multivolume World at War series, the starting point is a different outcome for a civil war battle with the implications playing out to a World War I that rages across North America with the Confederacy allied with Great Britain and the Union with Germany.

The Children’s War is of the “What if?” variety. It is set in a roughly contemporary time in which Germany won WWII. It might be compared to Fatherland, a murder mystery set in a 1960’s Berlin built as Hitler and Speer dreamed. One of the biggest challenges to this type of work is the manner in which the different time line is revealed to the reader. In the Children’s War, the only information about the “big picture” that is not revealed through the interplay of the characters is a political map of Europe showing the domination of Nazi Germany.

Several characters that will ultimately meet and interact are followed. Since the primary character is a slave laborer, who knows very little about “the big picture”, we also learn about it slowly. We also learn about his story in a non-linear fashion as he reveals it to others and learns it himself. Much of it is told through dreams and flashbacks. We first encounter our main character after he has been kidnapped after having escaped to Switzerland. The various circumstances surrounding the escape are revealed much later in the book. Only when his life is a stake, is he willing to reveal that he was raped by the commandant of his prison camp.

Peter or Alex, as he is variously known, took up with the English resistance as a teenager. His group was betrayed and rounded up. He was the only one to escape. He was ultimately picked up not for his resistance activities, but rather for having failed to provide the six years of mandatory labor required of English youth. Englishmen have some hope of being accepted as being worthy of Reich citizenship, the path chosen by Peter’s father and brother.

He ends up in the type of labor camp he would have served in, but for a longer term. Being older, he takes on something of a leadership role. He learns that the commandant has been raping the young men in the camp. He challenges him and the commandant agrees to stop. He does stop raping the young men, but now turns his sights on Peter, who ultimately complies. The sexual abuse by the commandant and learning that his sentence is effectively indeterminate motivate Peter to escape to Switzerland. In Switzerland, he is kidnapped, which is where the story begins.

Peter’s life is now forfeit. He will be allowed to live only as a slave. At his new camp, he is made something of a project. It is thought that he can be turned into an automaton through torture and psychological manipulation. The project is deemed successful and he is sent to live with a family as a domestic slave. There are several other stories being told that will ultimately converge. The author signals a shift in viewpoint by including a fragment of the closing sentence of one chapter in the opening sentence of the next chapter. This rather cute device is the only thing about the book that I find tedious.

We also follow the career of the man who will be Peter’s master for a period of time and, more significantly, members of the resistance. We learn that a remnant of the Polish Home Army has survived in a mountain redoubt and lives in an uneasy, unofficial truce with the Reich. Both sides refer to it as the protocols. They have managed to plant hidden bombs in key German installations which gives them a small amount of leverage. The Germans leave their mountain redoubt alone. They have a quasi-judicial process for determining when particular Germans have violated the protocols. They then assassinate them. Children raised in the redoubt are taught to speak formal unaccented German to facilitate infiltration. A few members are in very high positions in the Reich living a complex and dangerous double life.

Peter contrives an escape from his current master, a low-level functionary. He steals his car and just keeps driving. He stumbles on the mountain redoubt of the resistance. It is touch and go as to whether they will shoot him or not. Finally he is tentatively accepted. Along with the rest of his story he tells about having been raped.

The reaction of the Resistance members to him and his story are quite fascinating and give the story more “realism”. His integration with the Resistance people is not purely a matter of them getting to trust him. From time to time they are outright mean to him, merely because they don’t like him. He is from time to time taunted about having been raped. While he is on an undercover assignment his female companion asks him if he was dreaming about the Commandant. When he replies that he wasn’t she says that she thought he was because it seemed like he was enjoying his dream.

In the future, or present actually, envisioned by the author, America is like our culture on steroids. Peter is brought to America as something of a publicity stunt to talk about being a slave in Germany. In America, cigarettes are illegal. You can, however, buy them if you are a certified addict. Visiting Europeans are routinely granted the addict certificate since Europeans are known to smoke like chimneys. Peter is cautioned not to talk about being a rape victim. A man saying he was raped would likely offend women. Peter goes on a talk show with a black woman college professor. She lectures him that he could not possibly understand what it means to be oppressed since he is a white male. Her experience of slavery is more valid than his.

As the story unfolds, we will learn that Peter’s experience with the Commandant is not his only sexual relationship that was less than consensual on his part.

Despite some points where the willing suspension of disbelief is severely strained, The Children’s War is well worth reading. Besides showing the disabling results of rape, both from his own reactions and those who know what happens to him, it will help us to appreciate that we in fact live in Churchill’s “broad sunlit uplands”. It takes a glimpse of the new dark age in the light of a perverted science to appreciate it.