Originally published on Forbes.com.

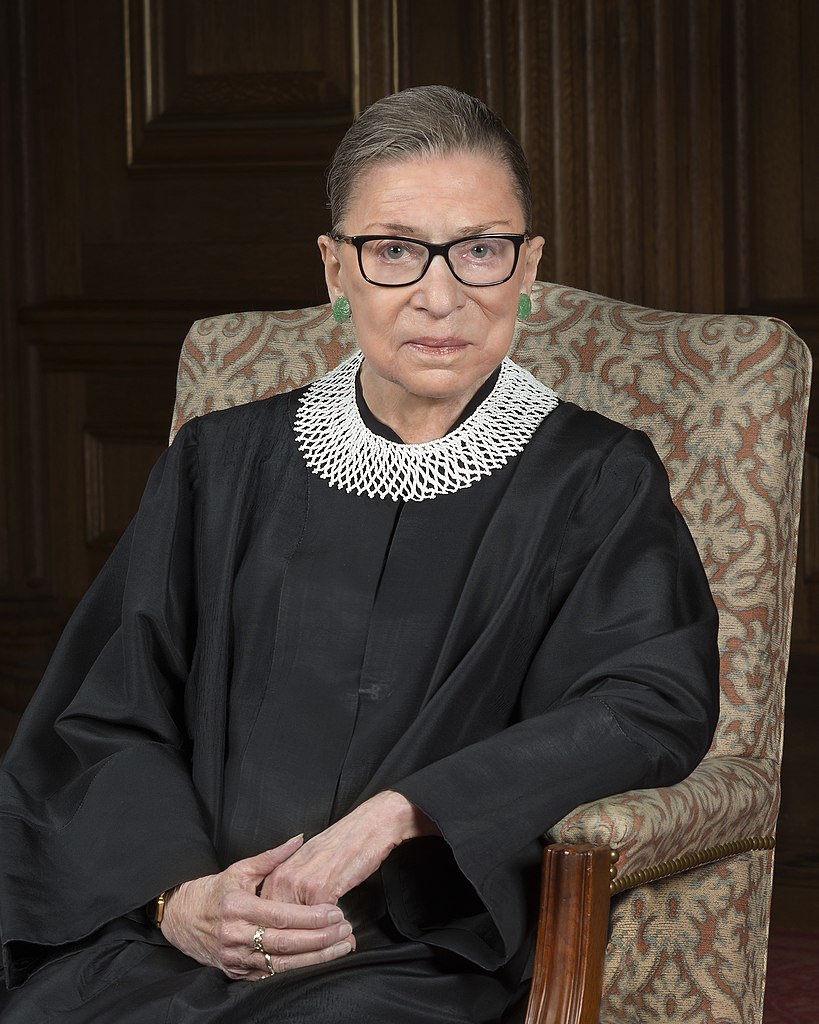

It never occurred to me that a Tax Court decision could star in a motion picture, but it has happened. The film has a pretty provocative title “On the Basis of Sex”, but they don’t mean it that way. Felicity Jones portrays a young Ruth Bader Ginsburg (RBG) (There had to be one unlike my Nanna Reilly who I am sure was always old) and Arnie Hammer as her husband Martin Ginsburg. I have it on very good authority that Martin Ginsburg was a first-rate tax attorney (See follow-up). And another star in the movie is a Tax Court decision. How often does that happen?

I haven’t seen the movie yet, but I have read the decisions (There was an appeal, which is where the Ginsburgs came in). The decision is Charles E. Moritz v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, which was decided by Judge Norman O. Tietjens in 1970 in favor of the IRS. Mr. Moritz had represented himself – not surprisingly given the low stakes. The decision was appealed to the Tenth Circuit where Mr. Moritz was represented by Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Martin Ginsburg backed up by Melvin Wulf of the ACLU and Weil, Gotshal & Manges. The lead attorney for the United States was James Bozarth played by Jack Reynor. Sam Waterston, who has played a lawyer on TV more than once, portrays Solicitor General Erwin Griswold.

The Tax Court Decision

As noted the stakes in the case were low. Mr. Moritz was contesting a $328.80 deficiency. He had taken a deduction under Code Section 214 – Expenses for household and dependent care services necessary for gainful employment. Mr. Moritz was an editor for the publishing firm Lea & Feibiger. He had an office in his home, but he had to travel extensively to meet with authors.

The travel required him to spend money to help care for his mother, who lived with him. She was 89 years old and confined to a wheelchair. Mr. Moritz hired Cleeta Stewart to help care for his mother. He paid her $1,250 of which $600 was attributable to the assurance of Mrs. Moritz’s well being.

Code Section 214 as in effect in 1968, the year in question read (emphasis added):

There shall be allowed as a deduction expenses paid during the taxable year by a taxpayer who is a woman or widower, or is a husband whose wife is incapacitated or is institutionalized, for the care of one or more dependents (as defined in subsection (d)(1)), but only if such care is for the purpose of enabling the taxpayer to be gainfully employed

Since Mr. Moritz had never married, he didn’t qualify.

Mr. Moritz argued that denying him and other confirmed bachelors the deduction was “arbitrary, capricious and unreasonable”. Judge Tietjens pretty much went with Reilly’s First Law of Tax Planning – It is what it is. Deal with it.

The purpose of this provision was: “to provide for a deduction for all working women and for widowers for the care of certain dependents.” clearly reflects this purpose by specifying who is entitled to the deduction. There is no ambiguity here nor is there a demonstrable intent to give relief, in the form of a deduction to all single persons. In fact, during the Senate hearings on the 1954 Code, there was testimony on the issue of allowing the deduction to all single individuals,

And then there is the constitutional argument.

We glean from petitioner’s argument a constitutional objection based, it seems, on the due process clause of the fifth amendment. Petitioner claims discrimination in that he, a single male, is not entitled to the same tax treatment under section 214 as other single persons, widowers and single women, are entitled.

The objection is not well taken. As stated previously, deductions are within the grace of Congress. If Congress sees fit to establish classes of persons who shall or shall not benefit from a deduction, there is no offense to the Constitution, if all members of one class are treated alike. …

The legislative history shows that Congress gave serious consideration before the enactment of section 214, to various points of view. Its action cannot be said to be arbitrary, capricious, or unreasonable. Petitioner is treated no differently from other unmarried, past or present, males. His remedy lies with Congress, and not in this Court.

As it happened Congress did act. The Revenue Act of 1971 made Section 214 more generous and provided that it applied to individuals. The section was repealed by the Tax Reform Act of 1976 and replaced with Code Section 21, a credit rather than a deduction.

The Appeal

The appeal to the Tenth Circuit was argued by the Ginsburgs. They split the oral arguments with Martin doing the tax piece and RBG handling the constitutional issue. Interestingly, the Tenth Circuit cited a Supreme Court decision Reed v Reed, that RBG and Melvin Wulf had also worked on. It overturned an Idaho statute that favored males in determining who got to administer an estate.

To give a mandatory preference to members of either sex over members of the other, merely to accomplish the elimination of hearings on the merits, is to make the very kind of arbitrary legislative choice forbidden by the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment; and whatever may be said as to the positive values of avoiding intrafamily controversy, the choice in this context may not lawfully be mandated solely on the basis of sex.

Following that logic, the Tenth Circuit held for Moritz.

We conclude that the classification is an invidious discrimination and invalid under due process principles. It is not one having a fair and substantial relation to the object of the legislation dealing with the amelioration of burdens on the taxpayer. See Reed v. Reed, supra, 404 U.S. at 76, 92 S.Ct. 251. The statute did not make the challenged distinction as part of a scheme dealing with the varying burdens of dependents’ care borne of taxpayers, but instead made a special discrimination premised on sex alone, which cannot stand

IRS Wanted To Throw In The Towel

In 1978, IRS issued Action on Decision 1978-19 (sorry can’t find a free link) in which the conclusion was going to the Supremes was not warranted.

Code section 214 was amended in 1971. Pub. L. No. 92-178, § 210(a), (1971). It was amended so as to allow the deduction to “individuals” who qualify regardless of sex or prior marital status. However, the amendment is effective prospectively only. Under the circumstances, continued litigation of the issue for prior years would appear unwarranted because of the small tax attributable to the issue and the questionable chances of successfully litigating the issue.

Apparently, the Solicitor General thought otherwise, but it went nowhere.

However, the Tax Division of the Department of Justice recommended that a petition be filed and the Solicitor General, on February 3, 1973, authorized certiorari. But, as noted in the caption, the Supreme Court denied certiorari

Foiled again McCoy.

Other Coverage

I tried reaching out to the real-life James Bozarth, but he was unavailable. The person in his office whom I spoke with was not aware that Mr. Bozarth had been portrayed in a film. He did clue me in that the “h” is silent, so watch out for that when you are watching the film.

Amy Zimmerman has a story about RBG’s reaction to the film, which she found generally pretty accurate.

Lila Thulin has The True Story of the Case Ruth Bader Ginsburg Argues in ‘On the Basis of Sex’ in Smithsonian.com. There is an interesting claim that I want to check out.

It was the first time a provision of the Internal Revenue Code had been declared unconstitutional.

That’s not quite as big a deal as it might sound. The tax law was not codified until 1939 and then recodified in 1954. In 1895, the Supreme Court ruled that the income tax was unconstitutional since to the extent it reached income from property it was a direct tax requiring apportionment. (Pollock v Farmers’ Loan and Trust Company) That’s why the Sixteenth Amendment needed to be passed.

A.O. Scott reviewed the film for the New York Times. He doesn’t even mention the Tax Court or what circuit was involved. I love the New York Times, but when it comes to their tax coverage, don’t get me started.

I was hoping for something from the most indefatigable chronicler of the Tax Court in all the blogosphere, Lew Taishoff, but he is passing.

Mr Reilly, I yield to no one in my admiration for Justice Ginsburg. But I report present cases only. I leave to you the Moritz case, and what will surely be a scintillating blogpost, which I eagerly look forward to reading.

Be sure to check out the trailer. The best line is around 1:05 when Felicity Jones remarks “I don’t read Tax Court cases”. RBG gave Ms. Jones credit for nailing the Brooklyn accent and I have to say that she sounded pretty good to me.

Follow-up

I learned about the film from a facebook post by Jack Townsend, who has literally written the book on tax crimes. Mr. Townsend knew Marty Ginsburg professionally. He gave me a couple of anecdotes, one of which concerns collapsible corporations, which you need to be both geeky and old to know about. The best one was short, though.

I was given a deposition as a tax expert. The attorney for side that had not engaged me started off the deposition this way (paraphrased and perhaps simplified because of the passage of time).

Q OK, Mr. tax expert what makes you so damn smart.

- I am not sure I can answer that question.

- OK, who is the smartest tax lawyer in the U.S.?

- Easy, Marty Ginsburg is, and probably the smartest in the universe as well.

Remember, I was under oath at the time and stating the truth as best I understood it

Ellen Aprill pointed me to Matin Ginsburg’s own account of the Moritz case that he gave in a speech to the ABA.

So Mr. Moritz’s case mattered a lot. First, it fueled Ruth’s early 1970s career shift from diligent academic to enormously skilled and successful appellate advocate – – which in turn led to her next career on the higher side of the bench. Second, with Dean Griswold’s help, Moritz furnished the litigation agenda Ruth actively pursued until she joined the D.C. Circuit in 1980. All in all, great achievements from a tax case with an amount in controversy that totaled exactly $296.70